(the kiss of midnight, 2025)

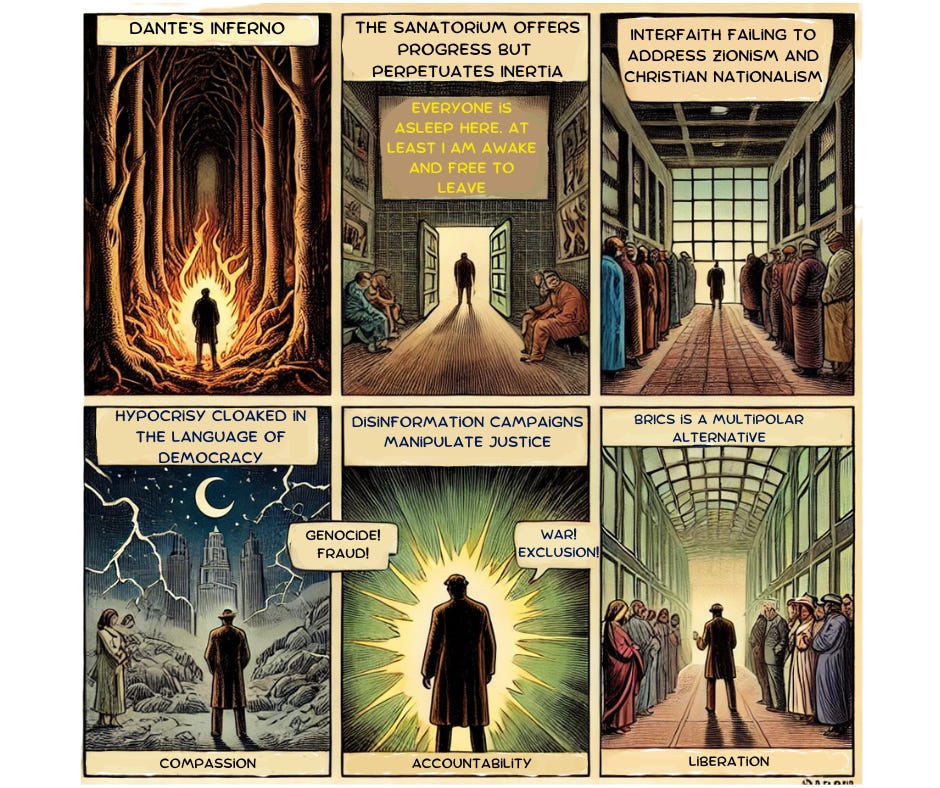

“In the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself in a dark forest, for the straightforward path had been lost.” (Inferno, Canto I)

Dante’s words are a haunting reminder of our collective state as we enter the new year. We find ourselves entangled in a moral and political wilderness where democratic and interfaith dialogue, once heralded as a beacon of unity, has too often failed to confront the worst excesses of religious dogma and its political manifestations. This failure has allowed Zionism to perpetuate genocide under the guise of divine sanction and has emboldened Christian Nationalism in the United States to champion land grabs, deny the climate crisis, and reinstate the abuses of colonialism under the mythos of Manifest Destiny.

These ideologies thrive not in isolation but as extensions of a fractured political and economic system that rewards exclusion, disinformation, and the erasure of histories inconvenient to its power. Yet interfaith efforts, grounded in historical materialist analysis, have served potent but often ignored gestures. Interfaith offers dialogue with the accountability of faith and solidarity within righteous belief structures.

To move forward, we must reject identity politics as a neoliberal tool of division, recognizing instead the shared material conditions that bind us. Intersectionality, properly understood, is not the juxtaposition of identities in competition but the weaving of struggles into a cohesive tapestry of resistance and renewal. It requires clarity: an honest reckoning with the past and an uncompromising commitment to dismantling the systems of oppression that perpetuate the abuses of capitalism, ecological destruction, and exclusionary politics. Houses of worship and faith-based institutions should have long ago abandoned religious dogma and theocratic absolutism, and do what it does best: provide communities with the tools to navigate their lives with the urgency of compassion, accountability, and liberation.

This is not a call for new conversations but for new commitments. Interfaith programs must embrace a praxis rooted in historical materialism, addressing the intersection of faith, politics, and economic systems with precision and purpose. This includes recognizing that the most vulnerable communities—indigenous, displaced, and marginalized— may have at one time been subject to religious conversion and oppression, but now hold the keys essential to liberation and ecological and social renewal. Their leadership must be central, not ancillary, to any organizational change.

In 2025, let us strive for transformation. The straightforward path may be obscured, but it is not lost. It can be found through courage, solidarity, and a refusal to be co-opted by the very forces we seek to overcome. We have the collective capacity to confront the realities of our time with an unwavering commitment to truth.

This last year was defined by profound contradictions. We found ourselves trapped in a sanatorium of contradictions, where the promises of democracy and liberation were revealed as hollow facades. The United States, for example, alternated between the chaos of electing a demagogue and the calculated violence of a president who arms regimes to commit genocide. In this sanatorium, the systems that claim to offer care and progress instead confine us in inertia, stifling agency and perpetuating harm. The promise of liberation—whether through the ballot box or international diplomacy—had become another form of entrapment, an illusion of freedom that masked the persistence of imperialist violence and systemic hypocrisy.

Conditions in the sanatorium are becoming daily more insufferable. It has to be admitted that we have fallen into a trap. Since my arrival, when a semblance of hospitable care was displayed for the newcomer, the management of the Sanatorium has not taken the trouble to give us even the illusion of any kind of professional supervision. We are simply left to our own devices. Nobody caters to our needs. I have noticed, for instance, that the wires of the electric bells have been cut just behind the doors and lead nowhere. There is no service. The corridors are dark and silent by day and by night. I have a strong suspicion that we are the only guests in this sanatorium and that the mysterious or discreet looks with which the chambermaid closes the doors of the rooms on entering or leaving are simply mystification.

I sometimes feel a strong desire to open each door wide and leave it ajar, so that the miserable intrigue in which we have got ourselves involved can be exposed.

Bruno Schulz “Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass”

Lost in a sanatorium is like being in a state of transition without clarity—a liminal space where the old structures of oppression persist even as cracks in their façade appear. We condemn Trump’s rhetoric but ignore Biden’s authorization of billions in weapons to destroy Palestinian homes, target hospitals, and perpetuate genocide in Gaza, while waging war and land grabs in Lebanon, Yemen, and Syria. The targeting of journalists, hospitals, and children by Israel is not incidental—it has been part of a broader strategy of annihilation that we enable with weapons, funding, and political cover. Our government and corporations largely support this genocide while feigning concern for human rights, and the complicity is staggering. This is not merely a failing of morality but a structural reality of imperialism: a system that requires war, oppression, and dehumanization to sustain itself.

In the Sanatorium, even the narrative of liberation is weaponized to justify the escalation of military aggression, not just in the Middle East but also against China. This ambiguity does not mark progress but rather the stasis of a system that feeds on war and division.

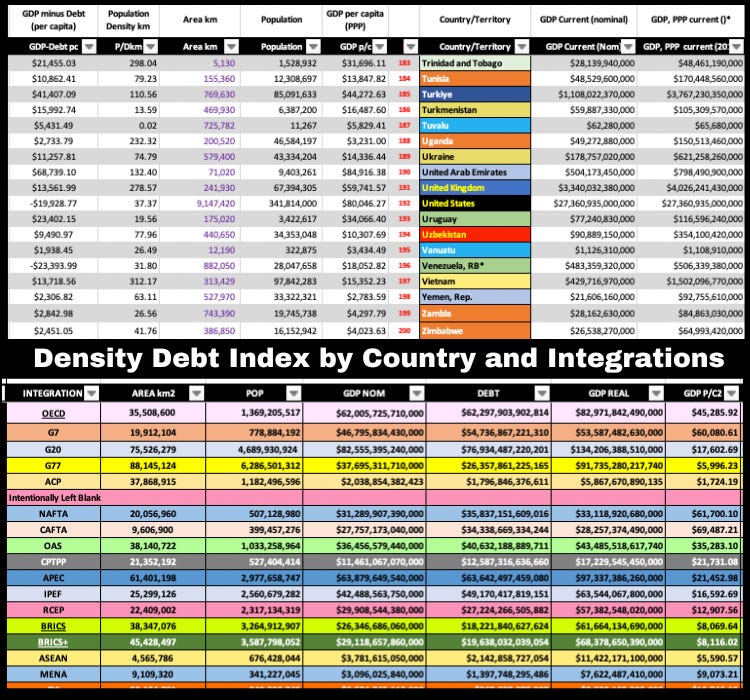

Information campaigns warp public perception of global shifts. We are fed narratives of China’s aggression while ignoring the U.S.’s provocations in the Pacific and the South China Sea. We are told to fear BRICS as a threat to “Western values” without examining how this multipolar bloc might overcome the challenges of dollar hegemony and provide alternatives to the predatory practices of the IMF, the World Bank, and discriminatory sanctions. Disinformation is not a flaw of the system; it is its backbone, keeping us docile, fractured, and asleep.

And yet, even in this Sanatorium, there are seeds of hope. The cracks in the old structures are real, and the possibility of transformation, though obscured, exists. But it requires confronting the illusions of liberation we have been sold and demanding accountability, not just for the obvious atrocities but for the systems that enable them. If there is to be liberation, it must come not from within the confines of this Sanatorium but from the deliberate dismantling of its walls. The hypocrisy of this system, which cloaks itself in the language of democracy and freedom, is not just staggering—it is systemic.

And yet, even for those of us who are awake, the feeling of helplessness looms large. Trapped in Schulz’s Sanatorium, we are left to wander corridors of inaction, aware of the machinery of destruction yet unable to stop it. The wires are cut, the bells do not ring, and we are left to question if anyone is even listening.

The only clarity we can hold onto is the historical materialist understanding of imperialism as the driving force behind these atrocities. It is imperialism that underpins the genocide in Palestine, the aggression in Yemen and Syria, and the disinformation about China and BRICS. It is imperialism that allows leaders to authorize war while chastising others for lesser sins, or to provoke wars like the proxy war between NATO and Russia taking place in Ukraine.

If we are to make 2025 anything other than a continuation of these horrors, we must confront this reality with unflinching honesty. As we fling open the doors of the sanatorium and expose the machinations of empire, we must resist the comfort of helplessness and embrace the struggle for understanding that imperialism is not inevitable—it is a system that must be dismantled.

The contradictions of this moment demand that we begin this new year not with false hope but with determination. Let us reject the untruths, expose the hypocrisy, and organize our world where mutual solidarity replaces empire, and justice replaces war.