In Mircea Eliade’s “Myth of the Eternal Return,” he describes a “terror of history” that at face value, exposes the difficulties of historicism as a cyclical series of repeated events that overflows with “evil,” with warfare, injustice, sufferings and annihilations. How do we contain the endless examples of violence and campaigns of terror, genocide, slavery, theft, fraud, exclusion and the ongoing dispossession of people from their land and resources? We would have had to be left out from the Enlightenment or the Age of Reason if we are to believe that the cycle of dispossession and abuse is part of a sacred natural cycle. How then are we to believe that laws and regulations that seek to compensate or criminalize abuses we discern as evil or unjust are controversial, unless there is embodied within the system a perverse notion of justice that privileges the accumulation of wealth and power.

While Eliade is often associated with his support for fascist or nationalist campaigns, his analysis over the sacred and the profane draws into question the very contradictions of whether we approach history as a system predetermined by cyclical cultural narratives or as a linear series of events. In his study, what Eliade does in his conclusion is tricky. As the rational solution for transcending the cycles of history, he introduces the Hegelian dialectic, the linear progression of thought and action promoting an ever forward advancing discourse of history. He then follows that up by expressing the spirit of the dialectic with the practical application of Marx’s program of historical materialism, anchoring the dialectic down to the practical conditions of labor, wages and the social sciences. Then, strangely, commensurate with his support of fascism, Eliade undermines the practicality of this logic by aligning Marx’s application as “militant,” as if the promotion of faith were an innocently benign program in the history of colonization and systemic inequality.

What Eliade refers to as the terror of history, is an existential trap that seeks to locate our will within the confines of the archetypes and repetition of primitive humanity. How we emancipate from that history, he concludes, “is through faith,” and that through faith, “everything is possible for man.” What is challenging about this program, is that we are already seeing the terror of history impose itself onto a world that is currently confronting its extinction. This existential trap can, on the one hand be viewed as a Thucydides Trap between China and the United States, where many in the west are pursuing campaigns for war as if it were already an inevitable conclusion for challenging the post-Cold War hegemony.

Simultaneously, reversing climate change is something that cannot be postponed and the primary reason that we remain stuck in this terror of history, in this multi-fisted assault against peace, is that there are forces that are invested in economic power that reject peace and reconciliation and seek to pursue the ongoing hegemony, despite all the evidence that squarely locates the cause of our global disenfranchisement on unfair economic practice.

If the context of reparations is to provide for justice, to equalize the impacts of our so-called evil, we should approach our relationship with time and history towards the practical matters that govern family, property, political, moral, judicial, economic and environmental organization.

Emancipating us from this terror of history requires us to understand what is most critical of history, and that is the perpetuation of systems that enforces conditions of racism, colonialism and slavery, and justifies genocides and ecological degradation. If the context of reparations is to provide for justice, to equalize the impacts of our so-called evil, we should approach our relationship with time and history towards the practical matters that govern family, property, political, moral, judicial, economic and environmental organization.

An accounting of restoration, much like an economics of history is only as tangible as how we value justice. This value is necessary if we are to stop the cycles of systemic violence that spiral with repetition through history as if it were an inevitable occurrence of anthropomorphic will. Restoration, as with reparation, restitution, or repatriation is not simply an acknowledgement of claimant’s rights for return or compensation, it is a recognition that if we are to heal our planet, relationships and interactions and move forward with peace, justice and reconciliation, we must acknowledge that the terror of history is a dark shroud that perpetuates systemic cycles of violence.

It is not enough to say, for example, that monetary compensation for seizures guided by the applications of misguided law is enough to reconcile generations of abuse, exclusion or land and resource theft. After all, the issue around systemic transgressions may not simply be resolved by individual arbitration claims, but rather by a restoring of rights and claims. One of the problems, however, is legal jurisdiction and simply deciding what law to interpret, what court, and what compensation may be insufficient for ending systemic bad behavior.

For a country like the United States, for example, whose evolution cannot be separated from genocide, slavery and dispossession, acknowledging this history does little for ending policies that perpetuate systemic racism, class struggle or gender inequality. Some of President Biden’s recent Executive Orders addresses this very issue by promoting diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility in the federal workplace and has already addressed the advancement of racial equity by supporting underserved communities in the Federal Workforce.

While the Federal Workforce only accounts for about 2 million people—or about 1.25% of the total workforce, the Executive Orders are at least an acknowledgement of the systemic failure of present-day Capitalism, and the abuses of liberalization in our trade, tax, and investment policies.

The admission of wrongdoing is simply a first step in restoring a pathway to dignity and justice. But even with an admission of guilt, there are far too many who continue to believe in the agency of power as being the justifiable motivation for perpetuating bad behavior. We must, as a matter of practical concern, regulate the bad behavior of ideologies that perpetuate the fiction of the Social Darwinist’s “survival of the fittest” trope, when its opposite—”mutual aid”—is the verisimilitude of our natural interactions, and the greater natural law.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital and Ideology reminds us exactly why, for example, the assault by conservatives in the United States wants to ban Critical Race Theory from the public school curriculum. Confronted by the extreme inequality of our present economic system, Piketty has provided us with the most inconvenient truth, which is that the dominant economic system is the inheritor of “slave societies”, of “colonial societies”, of “ownership societies.” If we are ever to move beyond the crisis of gross inequality, we need to rethink global economic strategies, beyond 20th century monikers that reinforce Cold War thinking. Such strategies are not only possible but should be the foundation for all decision making criteria. Additionally, the rubric against the promotion of implementing systemic change, is not a lack of Public Will, they are enforced. barriers like law, international treaties and a taxation system that does not allow for just and equitable redistributive wealth.

In practical terms, an economy of history and an accounting of reparations are intangible targets that may seem impossible to quantify in the context and otherwise disparate history of justice issues, particularly since except for some paltry examples for systemic compensation, history is bereft of systemic reparation schemes.

Addressing this lack of reparations– whether human or ecological– is there an approach by which quantitative indicators could be used to end the terror of history, the repetition of failed systems?

Lie stacked upon greed, buried beneath deceit, motivated by guile, hurled upon coercion, is neither commensurate with science nor philosophy. It is still a fictive conceit.

The very first principle to look at is economic. What kind of economic practice can we devise if the very foundation of our economic principles are predicated upon lies? When lie stacked upon greed, buried beneath deceit, motivated by guile, hurled upon coercion, is neither commensurate with the discipline and rigor of science and philosophy, it is still a fictive conceit.

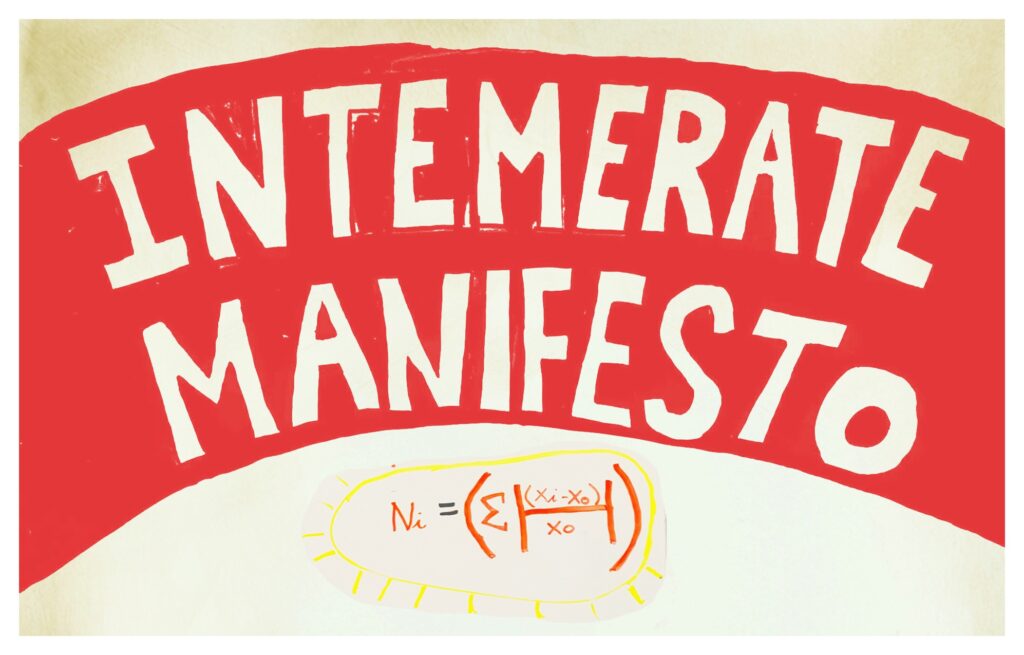

That the discipline of economics should rest so heavily on Malthus and Darwin and the faulty principles behind natural selection should give pause to anyone continuing to vouch the virtues of Free Market Capitalism. However, global societies have become so entrenched in this system that resolving this could itself be an extinction scenario. What is evident is that we need a transitional scheme that will minimize global disruption, and the way to achieve that is by adopting a new ecological accounting framework that is focused on mutual aid and development. When the United Nations adopted ecosystem accounts into the National Accounting System, they took the first leap. Now the question is what should this equation look like.

The intemerate equation is that nugget. It may not be the only tangible nugget that may be adopted, but it is a starting point by which we can use ecological accounts to repair the terror of history.

End