Video participation in Kehosa’s https://startupafrica.org/

transcript:

Restoring our ecological biodiversity, Reversing climate change, and Redistributing global wealth are the three biggest issues challenging ecological and economic justice. Intemerate Accounting is a post-growth initiative that could provide the systemic sea-change necessary to address this crisis in global governance. I will describe how this can be accomplished in some detail later, but I’d like to begin by stepping back and provide some broader context.

It is apparent that we are on the brink of global catastrophe. For some of us, this has been present for generations, and for a few, the global catastrophe is something some people sweep under the rug and save for later.

There are structures and choices expressed in our present system that valorizes rather than punishes ecocide, wealth and health disparities and perpetuates the kind of exclusionary practices that invokes this doomsday outlook.

It is also apparent that the crises that we are faced with is an existential conundrum. Peace achieved through War is a moral hypocrisy. How can we take pledges of good climate policies seriously if our leaders continue to provoke military incursions with the most reckless abandon? Demilitarization, de-occupation and decolonization—We cannot address post-growth if we continue to reproduce these very conditions that enable hegemony. We understand the mechanics of neo-colonialism-Kwame Nkrumah taught the world how the advanced economies continue to siphon Africa’s wealth. Now it is neoliberalism: the mechanics of privatization regimes, mergers and acquisitions, Nato, and debt—these structures perpetuate the conceit of colonialism.

When we consider the inherent wealth in Africa’s land, people, and resources, we all know that this is a region of tremendous potential that should play a much more dominant role in the global economy. And while the causes of Africa’s fragility factors are straight forward enough to identify, why have solutions been so evasive?

In terms of trade, the concentration of monetary wealth that is held by the global north is a huge factor, one that has limited Africa’s capacity to leverage its own development. As large as Africa is, it is still under a kind of containment and obstruction with goods-in-trade primarily filtering to the North.

While China’s Belt and Road initiative provides another option for Africa, it is once again the global north that is attempting to disrupt the physical connection with China through destabilizing access points with Syria and Yemen, for example, not to mention the obstruction campaign of Washington’s new Indo-Pacific maritime policy that pretty much seeks to undermine the real freedom of navigation by asserting a militarized maritime presence between Africa and China. When we look at a map, how is it that Africa’s maritime access for trade, both to the east and to the west, is constrained by this hegemony.

Are we ready to challenge the next wave of colonialism? The green economy is beginning to look a lot like eco-neoliberalism. The Pacific, and I believe Africa, the Caribbean, and many of the developing countries continue to face the same obstacles as they have for generations. Even now, as we head into the Glasgow Climate Summit, the proposals for reversing climate change might find tremendous financial opportunities for the Global North, but again, what about the Global South? Have the rich countries simply dragged their heels and waited for desperation so that they can leverage disaster capitalism? How do we move out from under the boot of this ongoing global theft and assert our shared equity on mutual terms?

These have been pressing questions for a long time, yet I remain optimistic because this time around the empire is in decline and multilateralism is renewed. Covid-19 has created a shift in our global consciousness, an awareness that the system has failed to produce the carrying capacity and promise of globalization and also because there are projects like Kehosa, promoting youth, food and water security, and rethinking what development should look like from the bottom up.

So while our ecological biodiversity is in crisis and global debt looms large—as severe as that is for developing countries, it is arguably worse in the advanced economies because the bottom has dropped out, and people are reaching for answers that they cannot understand. To put it bluntly, many people are in denial that their beloved free market system has collapsed. The accumulation of wealth has become so disparate and removed from the reach of working people, yet they cannot understand how these limits of capitalism is an unjust, unfair, inequitable, moral and ethical issue.

So, if this is all part of the geopolitical back story, I don’t want to mischaracterize my presentation by saying that Africa must choose between the neoliberal powers and China, or some of the other large markets like India or the Middle-East. I want to talk about a third option, the one that Kehosa is focusing on, and this third option is Africa. But what does that mean?

As a regional integration, the ratification of the African Continental Free Trade Area is one of the most substantial events of the 21st century. The opportunities for cross-border trade in goods and services, access to markets and supply chains is vast. But we must remember that this absolutely must include food and water security, access to health, our environmental protections, and greater inclusivity of women and youth.

So what I might ask, is how can a third way realistically transition Africa to participate in the global economy on these terms, and what would that take? What are the risks and the benefits? In terms of foreign direct investment, sure, but FDI is only as good as LDI: Local Direct Investment. Besides local manufacturing sectors, or cash crop export markets, when we talk about a local economy, we really are speaking about local practitioners, cultural ambassadors, artists, technological wizards, child care, house work the entire decolonized mindset that understands the true risks and benefits of sustaining local communities as well as managing our ecological biodiversity and revitalizing impacted communities. We cannot just speak about the profit margins of product accounts.

The recent release of Kenya’s Central Bank’s Annual Report seems to have surprised some China-Africa watchers in the west, particularly the focus on the trade deficit between Kenya and China. China’s exports last year was $3.08 billion and the first half of this year is 1.88 billion suggesting that this years total may be larger than last year’s. When you compare that to Kenya’s exports to China which was $139 million, those numbers seemed to have raised huge concerns because of this apparent deficit in trade. But I just want to ask why. Those numbers don’t mean so much when you consider that the billion dollar figures for machinery and transport will ultimately contribute to Kenya’s infrastructure.

The question I would pose is who better to have an infrastructure trade deficit with? The one who would seek to impose privatization of services and demand scheduled repayment on those loans, or those willing to extend the terms of those loans and are not interested in privatizing national capacities? In a nutshell, this is the situation between neoliberal debt and China debt. Countries need infrastructure, and you acquire infrastructure through loans.

The success of the AfCFTA is completely dependent on access and infrastructure and weighing the costs between neoliberal legal impositions that lead to vulture repayment schemes, and China’s win-win handshake, the west’s manufactured criticisms published through global corporate media chains is dishonest and simply hypocritical.

So let’s address trade sectors. Kenya’s current account in the goods trade is coffee, tea, horticulture, oil products, some manufactured goods, raw materials, chemicals, etc, and as is evident, Kenya has to compete with other African nations, who may have different tariff and tax structures. So, in the context where countries are forced to compete with their neighbors for market access, this situation really leads to a race to the bottom.

So I want to be clear that before the BRI and before the AfCFTA, there was very little opportunity for African countries to access markets on equitable terms. And now that the AfCFTA-BRI agreement is being worked out, there will be greater coherence and harmonization within the regional agreements, potentially setting much better terms that the AfCFTA can leverage. Certainly, this will provide far greater coherence opposed to countries having to compete with each other for access. Additionally, we’re going to find that the European Community and the US will also either have to compete with the BRI or try to undermine confidence in the agreement, which clearly, they have been trying to do.

So, if the benefit of the AfCFTA is to harmonize some of these kinds of costs and revenues and create more equitable conditions for trade that will help to raise the region, then it seems very clear that Africa’s regional motivations are well positioned to explore alternative positions for engagement

But understandably, to accomplish harmonization is not going to be easy as this cuts into the tax base of governments, some of whom may be more dependent on various goods and services than others. So while there’re going to be difficulties from local governments, any kind of deep market analysis is going to have to put people and environments first, creating conditions where local capabilities will have to align with expert capacity, but as long as we remain stuck within the corruption and resource curse of commodities pricing there is going to be very little opportunity for Africa to raise its position on the global stage.

So what I will demonstrate in the outline is that Intemerate Accounting is an achievable post-growth campaign promoting economic and ecological justice, like restoration, revitalization, and redistribution. We do this by leveraging our vast ecological data while ensuring that it is the people and communities that maintain the ownership of their data. The SDGs and Climate Agreements already have cabon-based investment plans on the table for creating value chains around our environmental data, but none that put people and their interactions with the environment first—none that come close to really valuing our ecological biodiversity.

How this can begin to happen—and I encourage anyone interested to contact me directly– will require the participation of one bank and the creation of one index,

and while I’m not going to explain the mechanics of how this can happen in this presentation, I will at least be able to communicate the kind of coordination that would need to happen that could lead to an African Third Way.

Lets put the Core Values of Kenya’s Central Bank to the test when they write that the Bank will “encourage, nurture and support creativity and the development of new ideas and processes.” Kenya’s central bank could be central in designing what the regulatory framework might look like for Africa and other regional groupings.

The key motivation that I am addressing is how to financially incentivize access and infrastructure to people’s health, to local and regional markets, to traditional and local stewardship, and to provide a fair, just and equitable way for the region to participate in the global economy through the practice of ecological stewardship.

Therefore, we must begin with another kind of accounting methodology that redefines and re-quantifies growth using indicators that developing countries and impacted peoples require.

Intemerate Earth is our campaign to transition our accounting system. This was initially developed in collaboration with the Pacific Conference of Churches which last year, culminated in the publication of a book called Ecological Economic Accounts: Towards Intemerate Values.

While I initially conceived of this as something that could be promoted through the ACP countries, it really was geared towards a program for Pacific Regionalism to address factors that kept the Pacific tethered to the colonial/post-colonial/neoliberal system. Then in 2020, when the Covid pandemic happened it didn’t take long to realize that this was so much more than a Pacific or an ACP construct. The world demanded change.

We began to explore alternative ways of telling this story, and mapping out an educational curriculum that could help to define how an intemerate transition could be accomplished in a way that does not create unwanted shocks to the financial system.

Here are characters that we made to highlight exactly how the equation operates and how peoples interactions contribute to the building of this framework. While it’s too much to go into right now, you can find it on our website, but suffice to say, our little accounting paradigm could really be that explosive, radical seed for global ecological and economic transformation.

We here is an example of how we mapped a curriculum that outlines the micro and macro coordination needed to implement and grow this framework, but what we lack is the kind of on-the-ground institutional support that could explore this more fully.

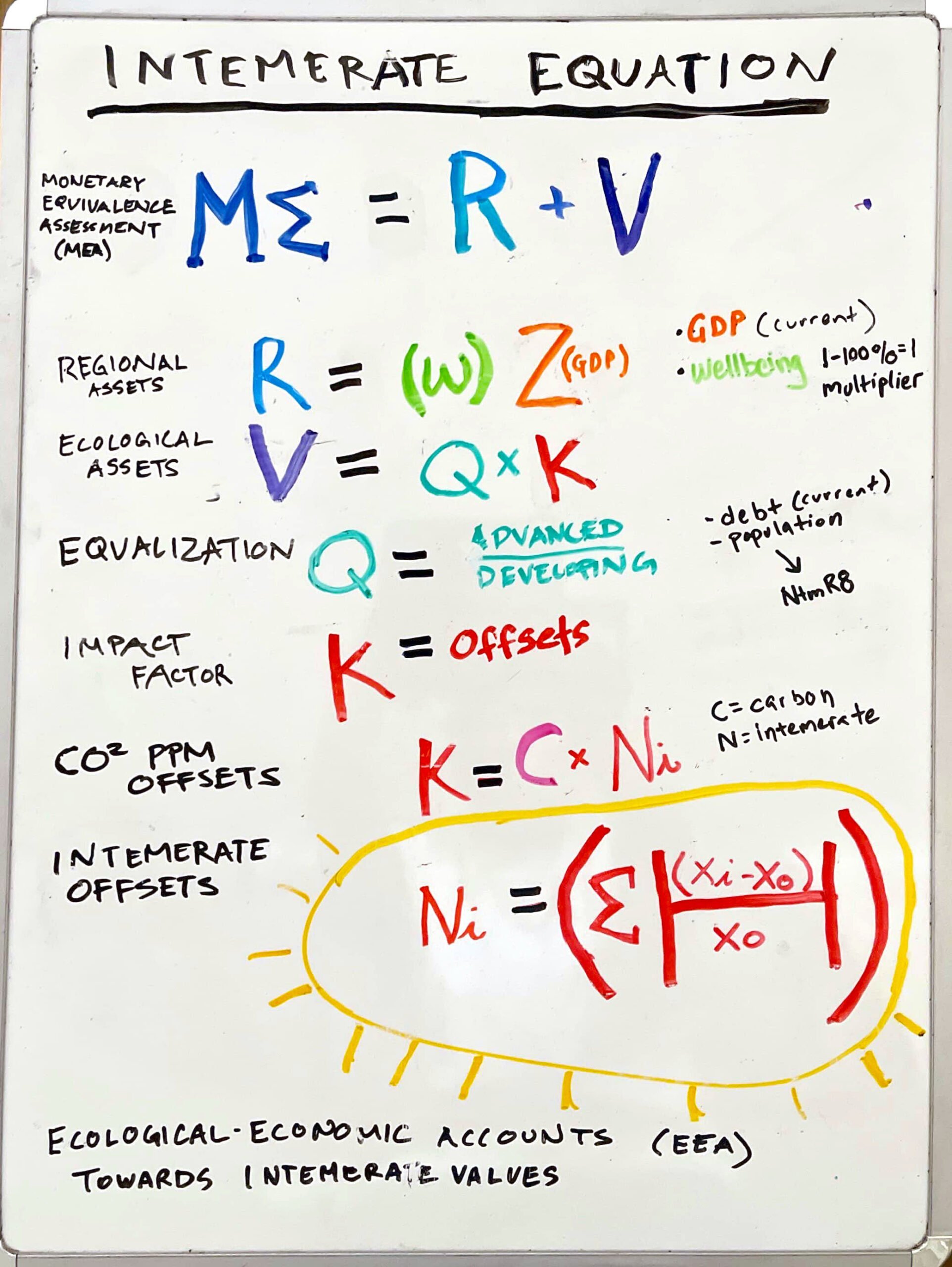

There are many alternative indicators being discussed right now, and new ways for accounting for GDP, but what makes the intemerate accounting equation unique is that it does not simply adjust national accounts by adding new environmental indicators. Because if all we are doing is adding new green or blue indicators, we will not be addressing the issue of redistributing wealth or moving away from the privatization or neoliberal framework. In fact, as I have mentioned, many of these new indicators could simply impose another top-down consent process for an eco-neoliberal economy, and is really a back door for perpetuating the same power structures to provide security, technology, monitoring, auditing, etc., thereby perpetuating the current system of exploitation and exclusion that we should be moving away from.

Intemerate Accounting is completely different, Firstly, we’ve created a more just way of measuring baselines; secondly we include a factor that allows for a relatively seamless transition away from the dominant GDP-based national accounting system towards one where Wellbeing indicators can modify our national accounts; and thirdly, we are inclusive of real-world market strategies that can make this financially viable for developing countries and underserved communities.

Typically, economic baselines are the starting point—or the base—from which to measure growth. From an economic perspective, baselines are set as a measurement of gains and losses. Baselines could be an absolute figure or a relative figure, but regardless all indicators that measure growth are determined by the baselines we set. They are the starting point.

The unique thing that the intemerate baseline does is that it inverts the starting point to be the goal and captures the incremental data towards restoring the baselines.

In the Pixar movie “Soul” that came out last year—coincidentally, the same month that the Intemerate Accounts book was published– the main character, after he “transitions,” has to wait in that long line to get into heaven, and then realizes that to get there, he has to reunite with his soul to repair his merit. We are in that kind of time. We need to reunite with our baselines–with our soul–and engage in an economy of reparations.

This inversion is a foundation for the kind of systemic reparations we need to break out of this cyclical terror of history. This reversal is a much better reflection for measuring environmental and social indicators, as it gives value to people’s interactions with ecological and wellbeing indicators rather than treating everything as a commodity.

This inversion is represented in our equation, with “n” representing the factor being restored. You can apply this to almost any environmental condition and record quantifiable data to meet the real world conditions for auditors and regulators.

And while I know this sounds like a very bold assertion, I would put it to the test in real world terms.

To make a claim that there is a tangible equation that can be used to restore our ecological biodiversity, reverse climate change, and redistribute global wealth sounds like hyperbole, or snake oil, or some magic fountain of youth, but it is not.

This is simply a mathematical formula that can be tested through input-output tables, measuring our interactions over time, calculating the rate by which restoration and rehabilitation can occur in quantifiable and relatively predictable terms.

Here’s an example that we looked at in the Munda province in the Solomon Islands regarding he restoration of a crab population.

Rather than a top-down commodity driven approach where environmental values are leveraged against carbon offsets for example, the intemerate baseline is a bottom-up approach where environmental values are determined by the interactions of local communities.

What could be better than local, indigenous, or customary processes developing and benefiting from their own services and technologies to meet their targets and goals on their timeline.

Imagine that by inverting the baseline, there could be a verifiable way to quantify our ecological interactions, and essentially own our data, while protecting the inherent wealth of environmental, health and wellbeing factors.

When we consider the accounting standards checklist for ESG or Environmental and Social Governance, we’re talking about a reporting format focusing on corporate governance around nonfinancial measurements for environmental sustainability and social impacts.

ESG, has not yet been standardized or quantified, which I would say is one of the objective goals in the current international climate and SDG meetings. And so the question remains, how do we quantify what is inherently unquantifiable?

Methods and standards need to be worked out, and the only solution that seems to be on the table is the worst one of all—the privatization, and valuation of our resources based on commodity scarcity.

Very briefly, I just want to say that Wall Street has recently created a commodity investment sector on water trades based on California water prices. It’s these kinds of utilities that appear to check off the environmental sustainability box in ESG reporting, but it does so at the expense of people and their rights to access. So I cannot help but wonder if much of the military base building near aquifers, or the licenses given to industries that contaminate our ground water, inflates the commodity scarcity pricing of water, and if it does, what does that do to how we access water?

As a bulwark to this kind of degradation and depletion, we could treat the Intemerate Equation as a financial index—like a stock index. But rather than it being managed by Wall Street, an intemerate index can be managed by the very same communities that are doing the work. This is particularly relevant as the IUCN recognizes the central and essential role of indigenous communities in stewardship and conservation of biodiversity. There is a high potential for creating new financial markets based on the measurement of our interactions rather than on the valuation of commodities, shifting the demand for extraction towards one that values service.

This data belongs to indigenous and customary rightsholders and stakeholders, not Wall Street fund managers.

This kind of data access could provide the triple benefits of sustainable livelihoods, decentralized local ownership and democratic participation. We aim to enable these kinds of conditions.

We all have the opportunity to measure, to count, to examine, to protect, to nurture, to analyze, to collect, to describe, to compile, to publish, to monitor and manage our environments.

This is a service that is certainly much older than capitalist and privatization regimes, and our local economies should benefit from these interactions.

What the intemerate baseline does is serve as a kind of verifiable guideline for regulators and auditors to mark the rate of restoration, to see whether communities are indeed attaining the goals they have set for themselves.

In light of the promise of optimism I mentioned in my introduction, I would like to respond to the Ask and Call-to-Action that is inscribed in the timeline, and end with a request: If Intemerate Accounting complements and catalyzes other initiatives to produce the post growth and post-colonial future that we want and deserve, then can we raise this math over the spectre of our current global governance?

Thank you