Sometimes, in the Worldhood of the World—at least as I understand Friedrich Heidegger’s chapter in Being and Time— naming something clarifies it for what it is. Naming carries the weight of recognition, forcing us to confront what lies before us. For example, we didn’t need the International Court of Justice to formally proclaim that Israel was engaged in genocide in Palestine. We recognize genocide as it unfolds in our time and across history. We recognized the slow genocide in Palestine for decades. For those who seek to look, we see it in West Papua by Indonesian occupation. We saw it in Darfur and Rwanda, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, during the Holocaust, and in Nanking. We recognize genocide in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the decimation of our First Nations peoples, including the occupation of Hawaiʻi. Obviously, naming these atrocities acknowledges their existence, yet it also indicts us for the inaction that so often follows such recognition.

The lack of reparations is, too, an example of this inaction. Of course reparations is the correct response to the atrocity of genocide, slavery, and dispossession, and it is easy to get bogged down negotiating a financial settlement, however, providing victims with access and infrastructure should be a no-brainer. The racism is still present, as is the evidence of occupation. The systemic structure of colonialism and neoliberal privatization inherent with capitalism is that the victors continue to revel in the spoils of their atrocities, until they can’t.

When we consider the liberalism that democracy evokes, we summon ideals like freedom of speech, equality before the law, individual rights, the rule of law, and popular sovereignty. These principles are enshrined as categorical moral imperatives, ideals that democracy claims as its foundation, as if they were innate and immutable birthrights. But what are we now, when these once-vaunted ideals are overshadowed by inaction, indifference, apathy, systemic hypocrisy, and moral complacency? If our supposed universal values are now selective and conditional, we have not only failed to uphold them but actively betrayed them.

Where does this leave us, except morally bankrupt, with systems that are inoperative, incapable of responding meaningfully to crises? We find ourselves displaced, not just geographically, as refugees or exiles, but existentially—estranged from the ideals we claim to hold dear. We are a society hollowed out by contradiction, proclaiming justice while perpetuating injustice, invoking human rights while trampling on them, championing democracy while silencing dissent. For many, we measure our democracy by what we consume, ignoring the fact that our consumption is the material manifestation of systemic exploitation, environmental destruction, and global inequity. It is the outward sign of an economic order that prioritizes profit over people, convenience over justice, and the immediate over the sustainable. Consumption becomes not just a personal choice but a political act, one that sustains the very structures of hegemony, extraction, and oppression that democracy claims to resist.

This moral displacement is not merely a failure of action but a failure of Being. In Heideggerian terms, it is a fallenness into inauthenticity, where we no longer engage with the truth of the world but are consumed by distractions, denials, and deceptions. Without a personal radical reckoning, without an acknowledgment of our complicity and a commitment to genuine restoration, we remain estranged from the world and for many, from ourselves.

The collapse of belief systems, particularly when tied to the ideals of justice, human rights, and environmental stewardship, is disorienting yet fertile ground for rediscovery and growth. The ongoing genocide and blatant occupation in Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Jordan with the support of our so-called liberal democracy reveals a moment in history that is not merely a crisis but an existential reawakening.

With all of its personal and immediate benefits, the distraction of social media, particularly the data hegemony associated with platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and X, has fundamentally altered how we engage with the world and with ourselves. These platforms are not neutral spaces for connection or self-expression; they are deeply embedded in systems of surveillance capitalism, commodifying our interactions, thoughts, and even our identities. They foster a false sense of community while fragmenting genuine relationships, reducing complex ideas to soundbites, and encouraging reaction over reflection. In doing so, they mediate our experience of the world in ways that diminish our capacity for authentic engagement and understanding.

“Perhaps we are here in order to say: house, bridge, fountain, gate, picture, fruit tree, window—at most: column, tower… But to say them, you must understand,

oh to say them more intensely than the Things themselves ever dreamed of existing. Isn’t the secret intent of this taciturn earth, when it forces lovers together, that inside their boundless emotion all things may shudder with joy?”

Rainer Maria Rilke— excerpt: “The Ninth Elegy,” Duino Eligies.

Approaching Heidegger now, with these distractions in mind, returning to the quiet and disciplined philosophical and poetic roots that shape our existential inquiries, feels both necessary and urgent. It is a means of resisting the shallow immediacy of our current moment, where attention is continually hijacked by algorithms designed to exploit our impulses rather than cultivate our thought. Heidegger’s meditations on time and Being offer a counterpoint to this frenetic culture. His insistence on Dasein—the grounding of human existence in Being-in-the-world—calls us back to a deeper, more deliberate engagement with the world and with ourselves.

In this return, we are reminded of the importance of dwelling—of lingering in thought, experience, and connection. Heidegger’s concept of temporality, where past, present, and future are intertwined, encourages us to see our actions and choices as part of a larger continuum rather than isolated moments of gratification or consumption.

In returning to Heidegger, we also return to the poetic—to the language and art that reveal the world as it truly is, not as it is mediated or manipulated. This act of returning is not a retreat but a way to resist, a way to reclaim the quiet, deliberate space necessary for confronting the existential crises of our time. It allows us to untangle ourselves from the web of distractions and rediscover the essence of Being-in-the-world, grounding our lives in thoughtfulness, presence, and purpose.

Our Interfaith Moment

In the beginning was relationship! Relationality is in our blood. We came into being through relationships. And it is through us that relationships will flow and continue. Therefore, as Pacific isalnders, we don’t just understand. We understand according to the rhythms of relationships, We don’t just interpret. We always interpret through the lens of relationships shaped by a particular Pacific Itulagi (lifeworld). Hence, we don’t just decolonise, Decolonisation is always fashioned by our particular relational worldviews.

—Relational Hermeneutics: A Return to the Relationality of the Pacific Itulagi as a Lens for Understanding and Interpreting Life— Upolu Luma Vaai

In the following quote on relational hermeneutics, I am reminded that the Pacific has had to re-engage with the colonial establishment of Christian doctrine with its own indigenous wisdom and world view. From the shore of the Pacific, the practice of interfaith is an extension of relational wisdom, rooted in the rhythms of connection and guided by the harmonies of indigenous lifeworlds, so very specific to the experience and identity of Pasifika.

This relational wisdom, deeply attuned to the interconnected nature of existence, mirrors Heidegger’s own insistence that understanding is never static but a dynamic process of interpretation. The act of not fully understanding, of grappling with the ungraspable, is central to a hermeneutic journey. Heidegger’s own approach to Being is fundamentally interpretative, requiring us to continuously reframe and re-engage with what it means to exist. This struggle leads to a solipsistic yet divine encounter, reflecting the very nature of Being as relational and dialogical—anchored in the ontic— the concrete or factual— crises of the world yet pointing toward something greater: the possibility of understanding our epistemological place in the chaos. This contradiction is not a failure but a fertile space for reflection. This is a process of unconcealment—where what is hidden emerges in moments of clarity, only to retreat again. The personal engagement with faith, philosophy, and crisis becomes a mode of Being that is open to the divine while remaining grounded in the material realities of global injustice.

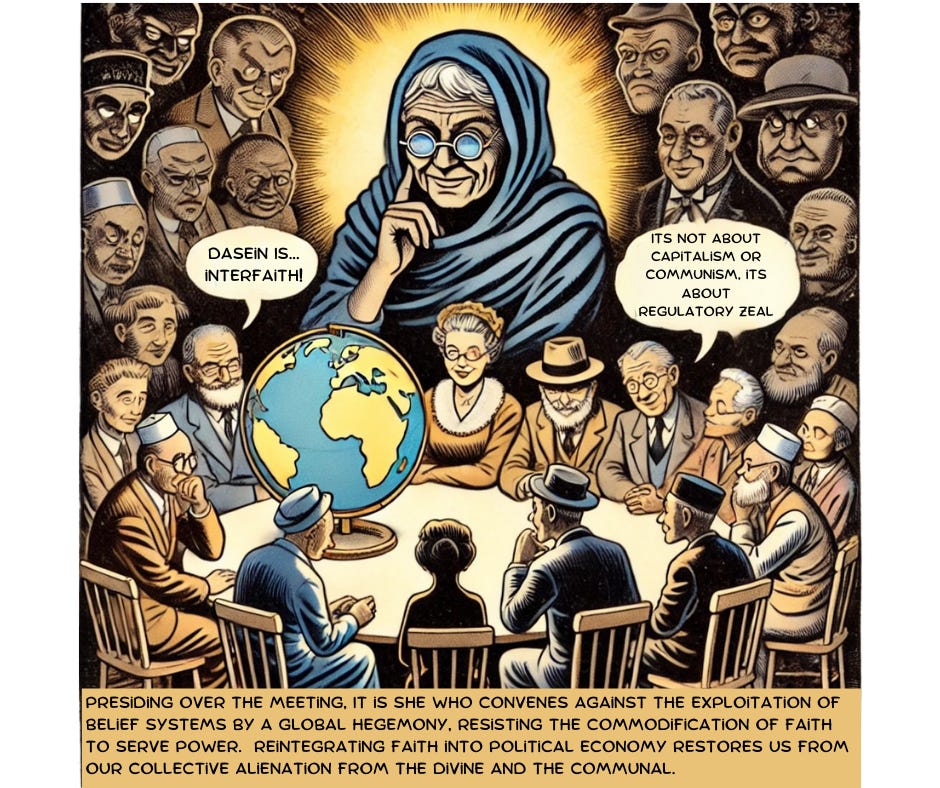

Interfaith dialogue and the role of houses of worship become central to this reflection, offering a critique of their absence or manipulation in the framework of political economy. This resonates with the ontological necessity of belief systems in shaping collective understandings of justice and resistance. Heidegger’s notion of worldhood underscores this, as faith traditions create networks of meaning that guide communities through existential crises and political oppression. Interfaith discourse as a pathway to resist hegemony aligns with the historical and philosophical roles of religious figures like Jesus and Mohammed, who can aptly be described as brothers against hegemony and injustice. Their teachings, pertinent to the resistance against imperialism, materialism, and social stratification, reveal faith as a profoundly political act. Similarly, Buddhism and Hinduism, with their emphasis on navigating suffering and injustice, provide frameworks for resilience and ethical engagement in a fractured world.

The exploitation of belief systems by global hegemony, and the commodification of faith to serve power, highlights a profound alienation from the divine and the communal. This alienation is central to the fallenness that Heidegger describes—where systems of meaning become co-opted, reducing authentic engagement with faith to mere functionality or control. This manipulation reflects the very crisis of Being that Heidegger warns against: a world where the sacred is eclipsed by the profane, and faith becomes a tool for domination rather than liberation. Yet, the irony is that the very figures and systems of belief rooted in justice are exploited to sustain injustice. This points to the necessity of reclaiming faith as a counter-hegemonic force. The ontological grounding of faith traditions, when authentically engaged, offers pathways for resisting exploitation and reorienting our collective systems toward equity and justice.

To argue for faith’s equal place within the framework of political economy is to challenge the modern separation of the sacred and the material. Heidegger’s emphasis on Being-in-the-world provides a philosophical foundation for this integration. Faith traditions, as expressions of worldhood, shape the relational totality of human existence. They influence ethics, governance, and community-building, and their exclusion from political economy reflects a profound misunderstanding of their ontological significance. Reintegrating faith into the discourse of political economy does not mean a theocratic imposition but an acknowledgment that systems of belief are foundational to how communities navigate crises and construct meaning. Faith, when authentically engaged, can counter the alienation and fragmentation wrought by neoliberalism and global hegemony, offering a framework for solidarity, resilience, and justice.

All this to say, the security of our humanity will not be safeguarded by the wrestling of political economies within the G20 or by the debates between freemarket capitalism and communism. However, if we center our collective indigenous and traditional faith networks within the framework of political economy, we might reclaim their potential to guide us toward collective liberation, navigating injustice with grounded and sacred resilience. The virtue of faith, of Dasein, is resolutely anti-imperialist, and only by supporting the remaining vestiges of decolonization will forge our human security forward, providing us with the regulatory zeal needed to manage what remains.