Disinformation about China “selling” TikTok or the Chinese government’s supposed authority over ByteDance reflects a strategic effort in international media to shape perceptions, often serving broader geopolitical and economic objectives. Such narratives not only misrepresent the reality of ByteDance’s ownership and operations but also play into larger efforts to undermine China’s standing as a global tech innovator.

By portraying Chinese companies as mere extensions of the state, these stories fuel skepticism among international consumers and investors, casting doubt on the independence and credibility of Chinese enterprises. This framing serves to justify policies like bans, restrictions, or forced divestitures under the guise of protecting national security, particularly in the U.S. and its allied countries. At the same time, it erodes trust in China’s burgeoning technology sector, deterring partnerships and discouraging foreign investment, effectively stalling the global momentum of companies like ByteDance.

China’s Approach to National Industries and Foreign Markets

Historically, China has been cautious and strategic about allowing foreign ownership of its State-owned industries. of which TikTok is not. This approach has been shaped by the following:

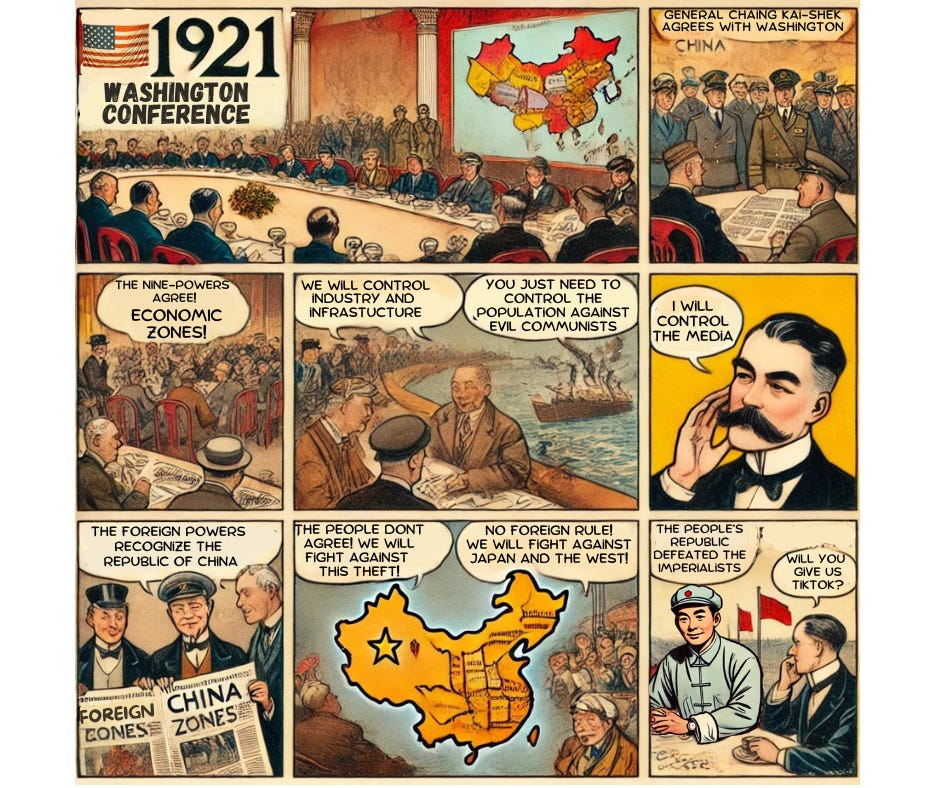

- Early 20th Century Colonial Influence and Resistance:

During the “Century of Humiliation,” foreign powers dominated China’s trade and industries through unequal treaties and concessions. These experiences instilled a deep mistrust of foreign control over national assets. To make matters worse General Chiang Kai-Shek—a puppet of Western powers—took over the Kuomintang (Republic of China) from Dr. Sun Yat-Sen, the progenitor of China’s revolution, and conceded to give away China’s key industries and infrastuctures to foreign control. - Post-1949 Nationalization:

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government nationalized key industries, emphasizing self-reliance and avoiding dependency on foreign capital. This set the tone for China’s guarded approach to foreign involvement in critical sectors. - Reform and Opening-Up (1978 Onward):

Under Deng Xiaoping, China opened its markets but maintained strict control over key industries, such as energy, telecommunications, and media. Foreign companies were allowed limited entry, often through joint ventures with Chinese firms. - Tech and Data Sovereignty in the 21st Century:

China views technology as a strategic industry and heavily regulates it, particularly in areas like social media, data storage, and artificial intelligence. Laws like the Cybersecurity Law and Data Security Law ensure that sensitive data remains within China’s borders.

ByteDance and TikTok

While ByteDance operates internationally, its headquarters are in Beijing, and it is subject to Chinese laws and regulations. The government has significant influence over companies like ByteDance, particularly when national security or data sovereignty issues arise. For example:

- Export Restrictions on Algorithms:

In 2020, China updated its export control laws to restrict the sale of certain technologies, including TikTok’s proprietary recommendation algorithm. This meant ByteDance could not sell TikTok without Beijing’s approval, effectively granting the government a veto over potential deals. - Strategic National Asset:

TikTok is considered a major technological success story, representing China’s ability to compete globally in social media. This symbolic importance makes China reluctant to allow outright foreign ownership.

Historical Examples of Foreign Ownership in China

China has rarely sold significant national assets to foreign markets. Instead, it has used partnerships, mergers, or limited foreign investment as a way to maintain control while benefiting from external resources. Some examples include:

- Joint Ventures in Automotive and Aviation:

Foreign automakers like Tesla have been allowed to establish wholly-owned factories in China (a rare exception to joint venture rules), but this is typically limited to industries where China sees mutual benefit. - HNA Group Asset Sales:

During financial difficulties, HNA Group (a private Chinese conglomerate) was forced to sell foreign assets, including stakes in hotels and airlines. However, these were external assets, not strategic domestic industries. - Lenovo Acquiring IBM’s PC Division:

Instead of selling a national company to a foreign buyer, Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM’s PC division in 2005 symbolized China’s preference for expanding its global footprint rather than reducing control.

Challenges of Selling TikTok

If TikTok were sold, it would likely occur under intense scrutiny from both Beijing and international regulators. Obstacles include:

- Data Security Concerns:

Both China and foreign buyers would worry about the ownership and storage of user data. - Geopolitical Rivalries:

Selling TikTok to a U.S. buyer like Elon Musk would risk being seen as a concession, potentially harming China’s image as a rising tech power. - ByteDance’s Autonomy:

ByteDance has resisted external pressure to sell TikTok, emphasizing its independence as a private company. However, it operates under China’s regulatory framework, which complicates its decision-making.

Broader Implications

China’s reluctance to sell TikTok to Musk aligns with its historical approach to protecting strategic industries and resisting foreign dominance. While ByteDance is nominally private, its ties to Chinese regulatory oversight mean any deal would require Beijing’s approval. This is less about direct “ownership” by the Chinese government and more about ensuring that strategic assets align with national priorities.

In essence, the situation reflects a tension between China’s goals of global technological influence and its need to safeguard sovereignty over critical industries. Historically, this strategy has allowed China to maintain a degree of control while benefiting from global markets, rather than ceding any of its industries, even at the expense of sanctions or a ban.

As such, Platform Capitalism addresses some of the most profound processes and pressing challenges of our times, including digitization, neoliberalization, financialization, globalization and deglobalization, uneven development, power, and inequalities, (in)security, the environmental crisis, and the role of finance in building more sustainable economies.”

—Bassens, D. (2024). “Finance in the age of geoeconomics: intersections of finance, production, and digital technology.”

Platform Capitalism

As a postscript, while it is both wonky and too long for this posting, I’m linking to a recent paper that highlights details of Platform Capitalism, one that highlights the Trump/Musk agenda for reshaping the rules of the global economy. The paper was recently published in Finance and Space, an “interdisciplinary journal focusing on diverse aspects of the spatial production of finance and the financial production of space.”

It is this very intersection between Global Financial Networks, Global Production Networks, and Global Digital Technology Networks, that demands over TikTok take place. This is not just technological warfare, this is existential for moving the economic needle back toward U.S. unipolar hegemony.